We used samples from the Big Wasp Survey to analyse the population genetic structure of the Common Yellowjacket, Vespula vulgaris across the UK. You can read the paper here (Open Access).

The Big Wasp Survey (BWS) is a citizen science project, set up in 2017 by Seirian and Prof. Adam Hart (University of Gloucestershire), that aims to improve our understanding of social wasps. Social wasps, comprising the yellowjackets and hornets, are ubiquitous across the UK (and indeed, across Europe, Asia and North America), yet surprisingly little is known about them when compared to other social insects such as bees.

The design of the BWS is quite simple: members of the public set up home-made beer/orange juice traps for a week in their back gardens, catch wasps, and send the contents in to UCL. Social wasps, especially at the end of the summer (when the BWS sampling takes place), go crazy for sugary substances. Until now, they had been raising their siblings within the colony (who provided them with sustenance, including sugary substances, converted from their own protein-rich diet). However, at this time of year, no more eggs are being laid. Essentially, the worker wasps are out of a job, hungry and bored!

Luckily for us, wasps really really like beer and orange juice. Over just a couple of years, the BWS has cumulated thousands of participants and tens of thousands of wasp samples and records, collected across Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The samples have already produced high quality species distribution maps of the most abundant social wasps across the UK, comparable with decades worth of data.

One way to improve our understanding of social wasps is to understand their population genetic structure. By using genetics tools, we can ask important questions to understand their dispersal: Do we find that there are genetically distinct, i.e. different subpopulations across the study area? If so, why is that? Are there any geographic barriers to wasp dispersal? How far can they disperse? Are these wasps genetically diverse?

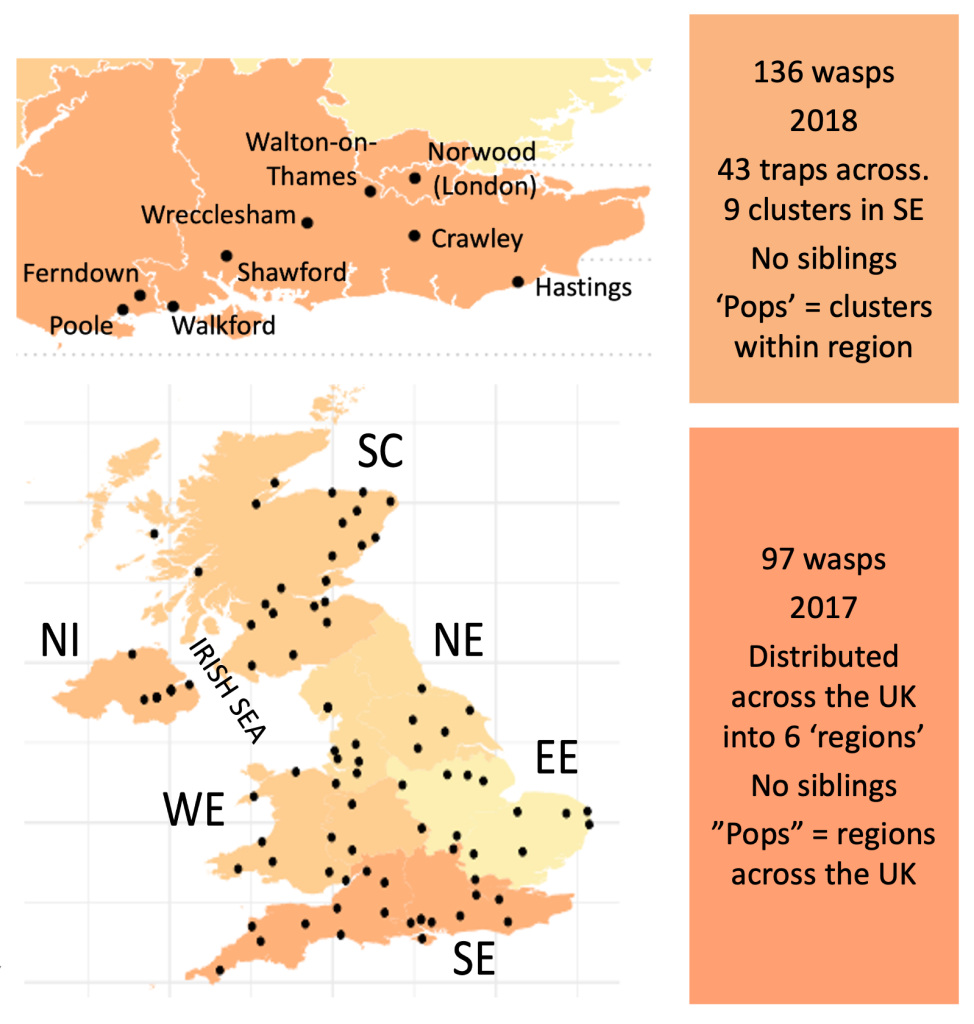

We therefore decided to try and use the BWS samples to delve into these hidden dynamics. We chose to perform this study on an abundant species to work on Vespula vulgaris, the Common Yellowjacket. But firstly, we needed to determine whether we could extract any genetic information, i.e. DNA from the wasps. Given that they were collected and handled in a rather unconventional manner (caught in beer, sent in the post, stored in freezers before being sorted and kept in ethanol…), we were not overly confident at first that this would be feasible/that we would extract enough DNA for our analyses. However, after a few trials, we were successful and were able to extract high-enough quality DNA from over 300 wasps. Victory! We then sent the DNA to be sequenced (transformed into a format so that we could read it and extract relevant information from it). Once we received this, we were able to analyse it.

We found that wasps do not show any signs of genetic differentiation across the UK, except between Great Britain and Northern Ireland. This demonstrates that they are very good at dispersing, except over significant water bodies, such as the Irish Sea. This isn’t surprising: we know that wasps are good dispersers, as demonstrated by various social wasp species in non-native ranges. Some of their ranges are expanding by tens of km every year.

How exactly wasps are dispersing remains questioned. Is it natural? Are they getting transported by the wind? Or is it human mediated? If the latter, it wouldn’t be the first time: invasive populations, such as the Asian Hornet Vespa velutina in Europe which originate from East Asia, are thought to have been transported to Europe in a plant pot. It may be a combination of the above, but the point remains: wasps disperse well, but are restricted by large bodies of water.

This study was the first of its kind for this species in its native range, and one of the first using samples collected by citizen scientists. Although social wasps can be highly problematic in invasive zones (see Vespula species in Hawaii, New Zealand, Australia, Argentina etc.), the fact remains that they provide important ecosystem services in their native ranges, including predation and pollination.

It is also fantastic to see how collaboration with citizen scientists can produce scientific studies that are published in peer-reviewed journals. Citizen science is an excellent way to produce more data. Especially in a (post-) Covid world, it has never been more important to find different ways to collect data. Who knows if there may be travel restrictions again in the future? Additionally, this allowed us to reduce costs and save time and money when collecting the samples.

A large proportion of this study was completed by four Masters students at UCL, three on the MRes Biodiversity, Ecology and Conservation course and one doing an MSci Zoology. It is therefore the cumulation of a large amount of work by these students, with the guidance of Seirian Sumner, Jinliang Wang, Emeline Favreau and Adam Hart. We are also highly grateful to the thousands of members of the public that have contributed to the BWS.

If you are interested in learning more about the BWS, feel free to check out the website.